George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

3 posters

Page 1 of 1

George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

I really, really love these long in-depth interviews he does. Fab photos too. I WANT that front cover.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

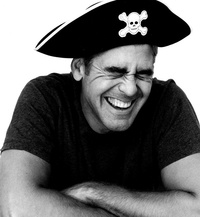

George Clooney When We Need Him Most

The actor, director, and GQ Icon of the Year is the one thing we can all agree on—at a time when we can’t agree on anything.

BY ZACH BARON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON NOCITO

November 17, 2020

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]All clothes, shoes, and accessories, his ownSuit, by Emporio Armani / Shoes, by Giorgio Armani / Watch, by Omega

George Clooney had neck surgery this morning, and they gave him fentanyl. “I'm out of it now,” he says, not seeming out of it at all. Clooney shows me the neck brace they sent him home with. It's the typical big white priest's collar thing, which he has decided not to wear, except when he needs some sympathy. Then he'll reach for the brace and put it on and grin like George Clooney.

The neck surgery was relatively minor, for a disk problem, but when the doctors got in there, they found all kinds of other stuff too. “It looks like arthritis, unfortunately,” Clooney says cheerfully. “Which: Hey, isn't it nice getting older?”

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

The disk problem was the result of a 2018 motorcycle accident Clooney had in Italy, or maybe it started before then. An interesting and perhaps surprising fact about Clooney, who projects comfort and ease like a lighthouse projects light, is that he's actually been in a significant amount of daily discomfort for the past 15 years. While he was shooting a scene in 2005's Syriana, someone kicked over the chair Clooney was sitting in, and he tore his dura mater, which is the wrap around the spine that holds in the spinal fluid. The spinal fluid was leaking out of his nose. Clooney has said before that he was in so much pain he contemplated suicide. He spent “three or four months really laying into painkillers,” he told me. Then he went to a pain guy.

The pain guy told him that the thing about pain is that it's just the body registering a departure from what it regards as “normal.” If you can train yourself to think of pain as normal, then the pain will cease to exist. “Basically,” Clooney says, “the idea is, you try to reset your pain threshold. Because a lot of times what happens with pain is you're constantly mourning for how it used to feel.” But Clooney is not the mourning type, and he'd sooner leak spinal fluid from his nose again than be maudlin or boring, so he tells this story about excruciating pain and the way he mindfucked himself out of it with a wry grin and a good deal of self-mockery, as he does most sad stories.

Clooney says it felt like “euphoria” when his brain finally tricked itself into feeling normal again. Then, a year and a half ago, while riding 75 miles an hour on his motorcycle to the set of Catch-22 in Sardinia, he hit a car. “He literally turned directly in front of me,” Clooney says. There is CCTV footage of the accident, and you can watch if you want. Clooney has. “I launched. I go head over heels. But I landed on my hands and knees. If you did it 100 times, maybe once you land on your hands and knees, and any other version you land, you're toast. It knocked me out of my shoes.” Literally. He lost his shoes. He also crushed the guy's windshield with his helmet. “When I hit the ground,” Clooney says, “my mouth—I thought all my teeth were broken out. But it was glass from the windshield.” He also knew, just from years of riding motorcycles, that any injury that involves ramming your neck into someone else's car generally results in paralysis, so he lay there “waiting for the switch to turn off.” But it didn't turn off. He was more or less fine, aside from whatever he did to his neck and his knees when he landed.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

[size=11]T-shirt, by Giorgio Armani

[/size]

I ask if he was in the air long enough to have had a profound thought before he came back down.

“You know, not really,” he says. “Although my kids were like a year old, and mostly it was just the thought that this was it and that I wasn't gonna see them again.” He says his wife, Amal, has since forbidden him to ride again, which he has accepted. “But I will remember, there is one moment.…”

Clooney wasn't alone that day. He was riding with his longtime friend and producing partner, Grant Heslov, and after Clooney landed on the pavement, Clooney says, “I was on the ground. I was really screaming. Like, really screaming. And Grant came back, and he was screaming at everybody to get an ambulance, and I remember everybody got out of their cars, they stopped in the middle of the street, and all these people came and stood over me and just pulled out their phones and started taking video.” At first, Heslov says, he thought Clooney was dead. “While we're waiting for the ambulance, I'm literally holding his head in my lap, saying, ‘It's okay, it's going to be fine,’ ” Heslov tells me. “Meanwhile there are people taking pictures.”

And here even Clooney gets somber for a second. “It's a funny thing. I'm not a cynical guy, and I really tend to look at life and try to find the good in everything. But I'll never forget the moment that what I thought might be my last few moments was for everyone else a piece of entertainment.”

Actually, Clooney says, he remembers one other thing about this day. It's what they were saying while they were pointing their phones at his bloody, wrecked body. He holds out his hands, summons up an exaggerated Chef Boyardee accent, and delivers the punch line that wipes away whatever sadness you might feel.

“They were like: A-George Clooney!”

He's in the living room of his house, the same three-bedroom house, situated on five acres, that he bought for $600,000 in 1995. Though I live just a few miles away, Clooney is keeping his distance. His son, Alexander, has asthma; Clooney is 59. There are enough risk factors on and off the property that Clooney hasn't left it much this year. He has been editing his newest film, The Midnight Sky, from here, and doing everything else too. “I cut my own hair and I cut my kids' hair and I'm mopping it and vacuuming and doing the laundry and doing the dishes every day,” he says.

“I feel like my mother in 1964. You know, I understand why she burned her bra.” But mostly he's happy—he's got a group text he calls a “chat line” that is busy 24 hours a day with his buddies checking in on one another, and he's got his family. “It kills me that I can't go see Bruce Springsteen in concert,” he says. “It kills me that I can't go see Bono, can't go see U2 in concert right now. But…you know, there's a lot worse things in the world. People are dealing with a lot bigger problems.”

His beard is rugged and snowy. His quarantine cut is the full Julius Caesar. His eyes, noble and recessed, look like something that should be on the side of a coin. He jokes about being old and looking older, but this itself is an old joke. Most of his best parts—going back to 1998's Out of Sight—have involved playing guys 10 years older than he is. He's tried it the other way—he and Paul Newman were once going to do The Notebook together, with Clooney in the part that eventually went to Ryan Gosling, playing the younger version of Newman—but it never works.

Clooney can't even play the younger version of himself. For The Midnight Sky, which he produces, directs, and stars in, he had to cast Ethan Peck, the grandson of Gregory, to play his character as a younger man. “We have similar eyebrows,” Clooney says, arching his.

He is in his living room because what used to be his combination bar and office is now a nursery for his twins. “It breaks a man down,” Clooney says, not looking at all broken down. “I sneak a bottle of tequila inside a couple of stuffed bears, just so I can go hang in the room every once in a while.” He does interviews and most other socializing—FaceTime dinners with his buddies, with candles and a glass of wine next to the laptop—right out in the open these days like the rest of us, slumped in a chair in a black T-shirt as his wife and children wander past and occasionally join in.

“Do you have kids?” he asks.

Not yet, I say. But we do have an open-floor-plan house.

“So you guys are right on top of each other,” he says sympathetically.

Yes, I say. We really are.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

Shirt, by James Perse / Sunglasses, by Ray-Ban / Watch, by Omega

“Yeah, my wife is literally— Like, today she's in the middle of sort of standing up against the British government, you know, deciding that they're gonna break international law. So she had to retire as the envoy, and she's in there doing that,” Clooney says, gesturing somewhere I can't see. “And I'm in here doing this interview.” He says this not to boast. He is just evidently proud: Amal Clooney has only hours before submitted a letter to the U.K.'s foreign secretary, resigning her post as the U.K.'s special envoy on media freedom in protest of Boris Johnson's intention, as part of the Brexit deal, to pass a bill that would violate international law and breach British treaty obligations. It's all over the news.

In The Midnight Sky, Clooney plays a ravaged, lonely scientist who believes himself to be the last surviving man on the planet until he locates a returning spaceship, full of living astronauts, bound for Earth. “Gravity meets The Revenant,” he calls it. Clooney gives a performance, in its stillness and sadness, that has echoes of characters he has played in The American and Syriana and even Michael Clayton—men sunk deep inside themselves and their past sins. The film is about regret, but it's also about the possibility of redemption; its stubborn optimism is what makes it a George Clooney movie. “I thought it was a very hopeful film,” he says about why he took it on. “I thought it was a film that said, ‘Although we may not get out of it alive, we might get out of it intact somehow.’ And I liked the idea of that.”

Felicity Jones, who stars opposite Clooney in The Midnight Sky, says she thought the search for meaning at the end of things had extra resonance for him, especially as the world began to fall apart this year. “We're all asking ourselves in this situation, ‘What is the point of our lives?’ ” Jones says. “I think for George, the fact that it taps into broader existential and philosophical issues was a pro.”

The Midnight Sky is also a reminder that Clooney, who has had one of the great acting careers in modern Hollywood, rarely actually appears onscreen anymore. Since 2014, he has taken on only a handful of roles, choosing instead to focus on directing. When he has acted, it's mostly been in his own stuff—2014's The Monuments Men, last year's television series Catch-22—because the presence of George Clooney in a project still goes a long way toward getting it made. His reasons for stepping back from most other acting jobs are complex and surprising, and in time we'll discuss them in detail. But at least one of those reasons is very simple, and that reason is that he feels great affection for his wife of six years and would generally rather spend time with her than do anything else. “I literally have never seen him happier,” Heslov, who has known Clooney since the '80s, tells me.

Clooney will tell you about Amal unprompted and then return to the subject again without ever having been asked. “I was like, ‘I'm never getting married. I'm not gonna have kids,’ ” he says. Clooney, whose 1993 divorce and subsequent bachelor years were objects of great and enduring tabloid fascination, says he was content with his life—more than content, even. Work was enough; it was more than enough. He'd decided: “I'm gonna work, I've got great friends, my life is full, I'm doing well. And I didn't know how un-full it was until I met Amal. And then everything changed. And I was like, ‘Oh, actually, this has been a huge empty space.’ ” Marriage changed him in the simplest way, he says, “because I'd never been in the position where someone else's life was infinitely more important to me than my own. You know? And then tack on two more individuals, who are small and have to be fed.…”

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

T-shirt, and belt, by Giorgio Armani / Jeans, by Levi’s / Sunglasses, by Ray-Ban / Watch, by Omega

And here, in fact, comes one of them now, bombing into the frame. Clooney's whole face lights up.

“Oh, hey! Here's Alexander. Here's my son. Come here! Say hi! Say hello! Say ‘Hi, Zach!’ ”

Alexander has a mop of brown hair and chaotic teeth and looks like the son of George and Amal Clooney.

Clooney gathers his son in his lap, and for a while he forgets about me and just talks to his boy.

“You've got chocolate on your face. Do you know that? What is that? Did you have chocolate?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah? You did? Hey, Alexander? Let's see. How old are you now—15?”

“No.”

“How old are ya?”

“Three. Because I got my birthday.”

“Yeah, you had your birthday! And do you speak fluent Italian?”

“Yeah!”

“Say something in Italian. Let's hear you say something in Italian. Say ‘It's very hot today’ in Italian.”

“Molto caldo,” Alexander says.

“Molto caldo!” Clooney repeats proudly.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

Shirt, by Emporio Armani

“I feel like over the last, you know, 10 or 15 years or so, I got to the point where I was like, ‘I can't sit around and try to prove to people what I can do as an actor.’ I'm much more comfortable in my own skin.”

Clooney, in casual conversation, has a way of making asides that prompt you to sit up and blink, like: “Having talked to Snowden,” meaning Edward, or “I talk with Vice President Biden all the time.” He is not bragging. He is describing his life. What you are glimpsing, in these moments, is the halo of a career so improbable, so dependent on luck and timing, that it will likely never be re-created. For instance, another aside: “Once ER hit, and 40 million people a week were watching the show—”

I interrupt to note that ER, the television show that first made Clooney a star, began in 1994. And yet, apparently, he still remembers the number of people who watched it, 26 years later.

“Well,” he says, “I mean, when you look at numbers now and 14 million is the number one show—it's hard to explain to people. A 10 p.m. show doing those kinds of numbers was just unheard of. And for me, it changed everything.”

Clooney was 33 and had already been acting for a while when ER first aired, but what he would experience next is the kind of fame and recognition that only a handful of people in the history of this country have ever been able to know or understand. He was the interest we all shared. Arguably, he still is: 40 million Americans have rarely come together on anything since, beyond presidents Barack Obama (good friend; they play basketball together) and Donald Trump (bitter enemy; “I have his phone number in my book. He was just a dude that came out to nightclubs in New York and chased chicks. I mean, that's all he was. He was this guy with bad hair who chased chicks and seemed funny”). Now, at 59, Clooney tends to the myth of himself, built and burnished over the years, and to his actual domestic life, which used to be lived between film sets and plummy talk show appearances and now is what makes him happiest. There are those who retire or otherwise disappear, and those who hang on tighter than they should, past when they should, but there are vanishingly few like Clooney, who is still here, albeit on his own exact terms, giving us something to agree on long beyond the time of us agreeing on anything.

Besides the life-altering fame engendered by ER, another legacy of the show, for Clooney, was more complex: For years, people thought he was a bad actor. David O. Russell, who directed Clooney in 1999's Three Kings, infamously told him on that set, “Why don't you worry about your fucked-up acting!” That anecdote comes from Clooney himself, as does another one, about Steven Spielberg, who once visited the set of ER, tapped the monitor after watching one of Clooney's takes, and told the actor that he might be a star someday if he could just stop moving his head all the time. There are acting mystics in Hollywood—Daniel Day-Lewis, for instance, who won the Academy Award for There Will Be Blood the same year Clooney was nominated for Michael Clayton—and then there are guys like Clooney, who for a while was known for the more humdrum art of showing up to a set and reliably hitting his marks or, worse, starring as the least loved Batman in the history of Batmen, a fact he cheerfully owns. “The only way you can honestly talk about things is to include yourself and your shortcomings in those things,” he says now. “Like, when I say Batman & Robin's a terrible film, I always go, ‘I was terrible in it.’ Because I was, number one. But also because then it allows you the ability to say, ‘Having said I sucked in it, I can also say that none of these other elements worked, either.’ You know? Lines like ‘Freeze, Freeze!’ ”

“For 36 years, I was the guy that if some kid popped up and started crying, I'd be like, ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ And now suddenly I'm the guy with the kid, you know?”

Clooney doesn't talk about acting much—perhaps because it would betray effort, which by nature he's not inclined to exhibit—but when he does, it's fascinating. He says that in the beginning his reputation for being an overly busy actor was earned. “I'd had some success doing smaller parts in television, and when you're doing smaller parts in TV, you're in general trying to fill it with stuff,” he says. “And so what Spielberg was right about was that if I was gonna be one of the leads on the show and people are gonna watch it through my eyes, then I needed to take away all of the tricks I'd learned for getting through not very well-written pieces. You know, you'd eat in a scene that's not funny, but if you're talking with your mouth full, it's funny.”

He starts describing the stages of acting, all of which he went through. “The first thing you see is everybody overacts,” he says. “You're trying to cry. Well, people don't try to cry. Actors try to cry. People try not to cry. Right? You're playing the event, which is always a mistake. Then you get a few years under you, and then you learn some skills, and then the next stage is you underplay everything. Nothing is specific. Everything is quiet and important and you're looking everybody in the eye when you talk to them.”

He recalls a day on ER, a scene in which it was snowing and a patient comes into the emergency room and they're covered in snow. “And each of the doctors who would come in would see the snow on 'em and go, ‘Is it snowing?’ And each of them would play it as if it was, you know, just the question. Like, with no opinion to it. ‘Is it snowing?’ ‘Is it snowing?’ And everyone would come in: ‘Is it snowing?’ ‘Is it snowing?’ And I watched this one actor come in, and he looked at the patient, just looked down, and goes, [in the most irritated, disappointed voice possible] ‘Is it snowing?’ And the difference in tone, the anger, that clearly he had a plan for the day and snow fucked it up, made it specific. And once it's specific, then that's sort of the third stage of acting to me.”

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

Jacket, by Emporio Armani / Shirt, by Giorgio Armani

And forgive me, but I'm going to keep quoting Clooney here, because how often do you get to see an actor of his caliber show exactly how he does what he does? He describes another scene, a hypothetical. “It's two people sitting on a park bench and they're talking, it's a guy and a girl, they're young, she's sexy, he's a good-looking guy, and all of the dialogue is about baseball. ‘Oh, Pete Rose can hit, can't he?’ ‘Well, I actually like Joe Morgan.’ ‘You like Joe Morgan? I like Ken Griffey.’ ‘Oh, really? Ken Griffey's good.’ That's the scene, right? But the event in the scene is the girl is there to pick up the guy, so everything changes, then. The way you talk about the baseball players, the way you look at each other, the pauses in between one another. So you're not just taking the dialogue and doing it—you're infusing the actual event. The event: You guys are there to try to fuck. Right? Let's say the director says that. That's what these characters are there to do. Now everything changes in the way you deliver those lines.”

Clooney says once he learned to understand the exact impression he was trying to convey, he got better at conveying it. (This is true about Clooney off-screen as well, I can attest; you watch him gauge his effect as he goes.) Other actors are different, he says, but that's how he does it. “Look, Daniel [Day-Lewis], who's one of our greatest of all time, he is fully submersive, and I can watch him do anything. But I could watch Spencer Tracy do anything just as easily, and Spencer Tracy's the guy who looks at his mark. Stares at his mark. Looks down at it—literally, like, puts his forehead down—looks at it for 30 seconds as if making sure he's got his feet exactly on the mark while he's talking, and then he looks up and talks to you. Never rehearses. And you can't take your eyes off of him, because everything he did was true. So there's a lot of ways to get there.”

Clooney has been nominated for eight Academy Awards and won once for his acting, in 2005's Syriana. “If I get hit by a bus today, they'd say ‘Oscar winner,’ ” he says. But some of his favorite roles, including in The Midnight Sky, are the ones in which he has tried to do as little as possible. “I remember doing The American, and it was like that,” he says. “The American was a version where it was all about: ‘How still can you possibly be?’ ”

That ability, Clooney says, to just be still—to do less, in all senses—is something that comes with age. “I'll give you an example of how this works,” he says, “and I'll use my aunt Rosemary”—the great Rosemary Clooney, of “This Ole House” and White Christmas—“who was a wonderful singer. And I would say to her, ‘Why are you a better singer now at 65 than you were when you were at 25, when you could hit higher notes, when you could hold them longer?’ And she goes, ‘Because I don't have to prove I can sing anymore. And because of it, I serve the material. If the material's good, I can sing, you know, Why shouldn't I…? and it's at a different pace.’ ”

And now George Clooney begins to sing, in a voice that is as nostalgic and comforting as a warm fire.

“It's [sings languidly] Why shouldn't I take a chance…? instead of [sings showily] Why shouldn't I take a chance…? She doesn't have to prove she can sing, so she can serve the material. And I feel like over the last, you know, 10 or 15 years or so, I got to the point where I was like, ‘I can't sit around and try to prove to people what I can do as an actor.’ I'm much more comfortable in my own skin. When you struggled for 12 or so years as an actor, when you get in, all you want to do is prove you can act and all the stuff you can do and show off all your tricks. And then as you ease into it, you kind of go, ‘Well, I don't feel like I have to prove anything anymore.’ ”

These days, that feeling of having nothing to prove has led Clooney to act less and less. “I can remember, I did, like, seven television series before ER. A dozen pilots. I'd done hundreds of episodes of television. So if, let's say, you're doing a season of ER, which is 22 episodes, and let's say a movie's two hours long and our episodes are an hour, that's basically like doing 11 movies a year, right? In terms of acting, in terms of all of the choices you're making as an actor, all those things. So you're getting to the point of saturation, of like, ‘Well, I've played it like this, I've played it like that, I've done this, I've done that, I've tried this, I've tried that.’ So as time goes on, you're starting to look around, going, ‘Well, how else am I gonna be involved in this business that I really love?’ I love this business. And I also don't want to be 60 and worry about what some casting director or some young producer or studio executive thinks about me anymore. I wanted to be involved.”

So, he says, he's chosen directing. “Directing is the painter,” he says. “Acting, writing, you know, those are the paints.”

I interrupt him again here. Respectfully, I say, this may be true for many actors, but many actors are not George Clooney. We only get so many Clark Gables and Gregory Pecks. Spencer Tracy, to name a hero of his. We only get so many icons. Maybe Clooney could be that too. Maybe he already is. So, I say, perhaps it's not as simple as being like, “Yeah, man, I did a lot of takes on ER. Time to do something else.”

“Well, but look at acting careers,” Clooney says. “It's a funny thing. Go back and look at some of the biggest actors in the world. And take the guys that I love the most, the Spencer Tracys or the Cary Grants, and look at the longevity of their actual careers and you'll find something really funny: 20 years—15 years, some of 'em. Some of 'em 25 years, maybe. They're not as long as you think they are. And part of it for me was actors are never in control of their own career. If you're lucky enough to be able to pick and choose, you can say no to crappy ones and say yes to the good ones, and I've done both. But as time goes on, it's boring to just be an actor.”

Can I ask you what became boring about acting?

“I'm not saying ‘boring,’ ” Clooney says, changing his mind a little. He points at me: “You watch movies. You get your screeners at the end of the year, you start going through them. It's hard to find 10 films that you go, ‘Wow, I get it, man. This is great.’ There are moments in films, lots of 'em, but a full film that you just go, ‘Wow, this is great’? It's not like there are that many out there. It's not like Michael Clayton comes around every day or O Brother, Where Art Thou? Out of Sight. You know, Up in the Air or The Descendants. There aren't that many. That's one every couple of years. And I'd like to work a little more than that, and I also—look, it's less about being bored about something and much more about loving the other elements. You know?”

I ask Grant Heslov about his friend's decision to step back from acting, to direct and otherwise live his life. “This is how he put it to me when I was trying to do something during the summer recently,” Heslov says by way of an explanation. He says Clooney proposed an exercise. “ ‘Let's sit down and try to figure out how many summers we have left,’ ” Clooney said. “ ‘Let's say we were 55 at the time. So let's say we have 25 more summers left—25 years, 25 summers. That doesn't seem like that many if you lose a whole summer, right?’ ”

[You must be registered and logged in to see this image.]

Suit, by Emporio Armani / Shirt, by James Perse / Belt, and shoes, by Giorgio Armani / Watch, by Omega

About a week later, Clooney and I are talking a few hours after the state of Kentucky has decided not to meaningfully charge or arrest the officers who killed Breonna Taylor, and Clooney looks legitimately anguished: sunk into himself and sad. Clooney is from Kentucky. His parents still live there, and he goes back regularly to visit them. “I can't believe it,” he says. “There's not even a manslaughter charge for a woman who was lying in bed and got shot to death.” He rubs his eyes. “Imagine if those were three Black officers and they kicked in the door of a white person's home and shot and killed the woman, the wife, in bed. Imagine that. Fucking ridiculous. You know, it's just infuriating.” He says he hopes that the protests in his home state remain peaceful tonight. Then, he says, actually: “You know, they talk about looting and stuff. Well, there have been an awful lot of Black bodies that have been looted for 400 fucking years. And…”

He sighs and trails off and massages his neck, into which he got an injection this morning. “I have to do another one tomorrow,” he says. “It's a little like the Tin Man with the oil can.” And we go on to talk about other things, but after we're done, Clooney will sit down and write an angry letter to Deadline about the verdict, or lack thereof, in Kentucky. “I'm ashamed of this decision,” he'll write.

Clooney has always been a letter writer, and sometimes an angry one. “I actually have these stacks of letters and things that my assistant calls George Versus the World,” he tells me. Just the other day, he says, he responded to someone in Saudi Arabia who was asking for permission to edit The Monuments Men for screening there. And they wanted to cut out some of the explicit language, which Clooney was fine with, “but then at the bottom it said, ‘and we want to blur out the Star of David in these three shots.’ And I wrote a really scathing letter two days ago where I just said, you know, ‘I've been doing this a long time, and no one in my life has ever asked me to blur out particularly a Star of David in a movie that's about the stealing of art and then the mass murder of Jews.’ And I just said, ‘So the answer is: No, you can't have the film, and no, we won't be making any of these cuts, and go fuck yourself.’ ”

Clooney gently misquotes John Lewis, saying he's always taken pride in picking “good fights,” and this is true. The list of former Clooney enemies—though not particularly long—is extremely deserving: TV Guide, for its habit of omitting Eriq La Salle, ER's most prominent Black cast member, from its covers back in the day; Russell Crowe (“Just out of the blue, he's like, ‘I'm not some sellout like Robert De Niro and Harrison Ford and George Clooney.’ I'm like, ‘Where the fuck did that come from?’ ”); a Washington Post film critic, for suggesting that Clooney's Confessions of a Dangerous Mind was actually directed by Clooney's friend Steven Soderbergh (“At the end of the letter, I said, ‘Letter actually written by George Clooney’ ”). But, he says, these days he's mostly ceded the fights to other people. “I have much more fun watching Chrissy Teigen,” Clooney says. “Somebody steps into her world and you go, ‘Oh, I wouldn't do that, dude.’ It's so much fun. Like somebody who thinks they're really smart, and you just go, ‘Ugh, dude. You brought a knife to a gunfight.’ ”

But Clooney has always seemed to understand that celebrity is a game to be played, rather than a burden to be endured. It's not a coincidence that the most successful franchise he's been a part of was the Ocean's trilogy—three films built around movie stars playing glamorous people in lavish locations. Clooney is the rare person who makes fame seem fun—an opportunity for mischief and adventure. He has used his voice for innumerable just causes; he has also done things like hand out noise-canceling headphones to fellow airline passengers, for use in case one of his twins started wailing midflight. (“For 36 years, I was the guy that if some kid popped up and started crying, I'd be like, ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ And now suddenly I'm the guy with the kid, you know?”) In 2017, his good friend Rande Gerber went on MSNBC and told a story about how, years earlier, Clooney had summoned 14 of his closest friends and given them each a million dollars, in cash, in a suitcase.

Clooney has never really confirmed or denied doing this, and when I ask him about it, he rummages around for a moment and, for the first time since he initially showed it to me, comes up holding his neck brace. He wraps it around his neck, the big white priest's collar, and grins silently. But in the end he can't resist a good story, and so he tells it anyway.

“Amal and I had just met, but we weren't dating at all,” he says. “I was a single guy. All of us were aging. I was 52 or something. And most of my friends are older than me.” This was 2013. Gravity was just about to come out, “and because they didn't want to pay us, they gave us percentages of the movie, 'cause they thought it was gonna be a flop, and that ended up being a very good deal.” So he had some money—though not, interestingly, as much as he has now; Clooney's biggest financial windfall, from the $1 billion sale of Casamigos, the tequila company he started with Gerber and another friend, wouldn't come for four more years. But in 2013, he didn't yet have a family, nor any real idea or hope that someday he would. “And I thought, what I do have are these guys who've all, over a period of 35 years, helped me in one way or another. I've slept on their couches when I was broke. They loaned me money when I was broke. They helped me when I needed help over the years. And I've helped them over the years. We're all good friends. And I thought, you know, without them I don't have any of this. And we're all really close, and I just thought basically if I get hit by a bus, they're all in the will. So why the fuck am I waiting to get hit by a bus?”

The next step was how do you lay hands on $14 million in cash? And Clooney did some research, and what he found was that in downtown Los Angeles, in an undisclosed location, there is a place you can go, “and they have giant pallets of cash.” So Clooney got an old beat-up van that said “Florist” on it, like he was in a heist movie, and he drove downtown, and he got in an elevator with the florist's van, and he took the van down to the vault and loaded it up with cash. He told no one but his assistant “and a couple of security guys that were shitting themselves. And we brought it up, and I bought 14 Tumi bags, and then I packed in a million bucks, cash, which isn't as much as you think it is, weight-wise, into these Tumi bags.”

The next day he had all his friends come over. “And I just held up a map and I just pointed to all the places I got to go in the world and all the things I've gotten to see because of them. And I said, ‘How do you repay people like that?’ And I said, ‘Oh, well: How about a million bucks?’ And the fun part about it was: That was the 27th, the 28th of September. A year later, on the 27th of September, just by happenstance, was the day I got married.”

And this is a story about a charmed life, of course, but it's also a story about a guy who is doing his best to keep it that way, to liven up the days, to give himself more stories to tell before his time is up. “You know, it's funny,” Clooney says. “I remember talking to one really rich asshole who I ran into in a hotel in Vegas—certainly a lot richer than I am. And I remember the story about the cash had come out, and he was like, ‘Why would you do that?’ ”

Clooney smiles. “And I was like, ‘Why wouldn't you do that, you schmuck?’ ”

Zach Baron is GQ's senior staff writer.

A version of this story originally appears in the December/January 2021 issue with the title "George Clooney When We Need Him Most."

Admin- Admin

- Posts : 2188

Join date : 2010-12-05

annemarie- Over the Clooney moon

- Posts : 10309

Join date : 2011-09-11

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

Clooney wasn't alone that day. He was riding with his longtime friend and producing partner, Grant Heslov, and after Clooney landed on the pavement, Clooney says, “I was on the ground. I was really screaming. Like, really screaming. And Grant came back, and he was screaming at everybody to get an ambulance, and I remember everybody got out of their cars, they stopped in the middle of the street, and all these people came and stood over me and just pulled out their phones and started taking video.”

At first, Heslov says, he thought Clooney was dead. “While we're waiting for the ambulance, I'm literally holding his head in my lap, saying, ‘It's okay, it's going to be fine,’ ” Heslov tells me. “Meanwhile there are people taking pictures.”

And here even Clooney gets somber for a second. “It's a funny thing. I'm not a cynical guy, and I really tend to look at life and try to find the good in everything. But I'll never forget the moment that what I thought might be my last few moments was for everyone else a piece of entertainment.”

This part of the interview struck me the most. The fact that somehow we're not able to see others as human beings, but rather as just a bit player in the film of our own lives. I'm kind of horrified.

I'm drawing a kind of parallel between this and the biggest story from this interview that's doing the rounds about George giving his friends $1m each. I can't tell you how many begging emails and messages are coming through to me from people claiming that he could give them money too. Some people are even quite upset that he gave to his friends and not to charity (somehow managing to miss all the charitable work he's done the past couple of decades).

They just seem to see him as a bank, whose great pleasure it should be to just give them money.

Admin- Admin

- Posts : 2188

Join date : 2010-12-05

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

o, I noticed that, but there definitely seems to have been some comeback from people who

do know how much he does. There's no telling who you get to comment on a Fail article - and

what the depth of their knowledge is!

party animal - not!- George Clooney fan forever!

- Posts : 12431

Join date : 2012-02-16

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

Re: George Clooney interview with GQ magazine. Nov 2020

Here's the original story - via Rande Gerber in 2017............

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

party animal - not!- George Clooney fan forever!

- Posts : 12431

Join date : 2012-02-16

party animal - not!- George Clooney fan forever!

- Posts : 12431

Join date : 2012-02-16

Similar topics

Similar topics» George Clooney interview with Empire magazine - Nov 2020 issue

» George Clooney interview with Jimmy Kimmel - Dec 2020

» George Clooney on the cover and interview - Fly on Magazine

» Celtic Life Magazine: Interview with George Clooney

» George Clooney interview in the last Omega lifetime magazine

» George Clooney interview with Jimmy Kimmel - Dec 2020

» George Clooney on the cover and interview - Fly on Magazine

» Celtic Life Magazine: Interview with George Clooney

» George Clooney interview in the last Omega lifetime magazine

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

» Clooney voices pro-Harris ad

» 2024 What George watches on TV

» George's Broadway Dates Announced

» George sells his LA home

» Oct 2024 Clooney dinner Party

» My Wolfs review

» Happy Tenth Wedding Anniversary to George and Amal

» 2004 more Pranks that Alex does